Soaring energy prices and the cost of living crisis are sparking talk of an economic phenomenon not seen since the 1970s: stagflation.

But what is it – and is there any danger of it hitting Australia’s economy again?

Stagflation is a combination of the words ‘stagnation’ and ‘inflation’. Stagnation refers to a period of weak economic growth while inflation describes rising prices that cause the purchasing power of money to fall.

So, stagflation is when the economy doesn’t grow, but the costs of living do. To make matters worse, stagflation is typically accompanied by rising unemployment.

For many decades, this toxic combination was thought impossible – as inflation and unemployment are assumed to be opposites, according to Keynesian economic theory.

The theory posits that when unemployment is low, inflation should rise fuelled by rising wages, strong economic growth and high demand. The reverse should also be true – with sluggish economic growth leading to a drop in consumer demand, slowing inflation.

Normally, this is what happens. But, as the 1970s showed, every once in a while, high inflation can coexist with a weak job market and a sluggish economy.

What happened in the 1970s?

During the 1970s, tension in the Middle East pushed up the cost of fuel, with prices quadrupling over 1973-74. At the same time, many countries’ economies were sluggish, following decades of growth in the post-World War II era.

Naturally, higher oil prices sent inflation through the roof as the cost of manufacturing and transport rose. This, in turn, limited economic growth further.

Are we seeing the same dynamics today?

Admittedly, some of the same ingredients that led to the 1970’s stagflation are around today. The supply-chain crisis is increasing the cost of goods, while the war in Ukraine is causing a rise in commodity prices and dampening global economic growth.

However, that’s where the similarities end.

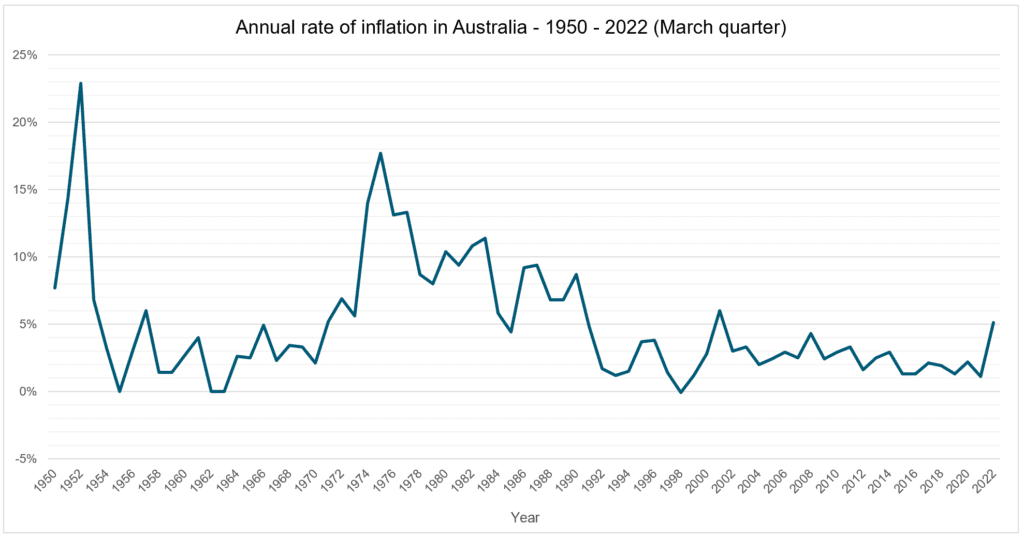

Take annual inflation. True, it hit a 20-year high over the March quarter at 5.1%. However, that’s nowhere near the 17.7% peak in March 1975, which was triggered by the oil price shock.

Meanwhile, the jobless rate was 3.9% in May, a 48-year low, while GDP figures show our economy is strong with growth of 3.3% through the year to March.

Australia seems to be facing the classic Keynesian scenario of economic growth and price growth going hand in hand, rather than the stagflation scenario where they move in opposite directions.

Inflation and rising interest rates

While stagflation is unlikely to be on the cards, Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe has said he expects inflation to hit 7% by end of the year.

As a result, more interest rate hikes are all but guaranteed as the RBA acts to take the heat out of the market. As a result, borrowing money will become more expensive and variable-rate mortgage repayments will rise (assuming lenders pass on the increases).

That said, it’s important to remember that while interest rates are rising, they remain low by historical standards. Depending on your financial circumstances, there are also steps you can take to get ahead of rate hikes, such as refinancing.

If you would like to discuss your personal or business situation, please reach out for a confidential discussion.

This article was first published in Personal Wealth Adviser, Issue 3.